Symptoms, Types And Treatment Of Spinal Tuberculosis

Understand the symptoms, types, and treatment options for spinal tuberculosis. Learn how early diagnosis and proper care can help manage this serious infection effectively.

Written by Dr. Md Yusuf Shareef

Reviewed by Dr. D Bhanu Prakash MBBS, AFIH, Advanced certificate in critical care medicine, Fellowship in critical care medicine

Last updated on 13th Jan, 2026

Introduction

Persistent back pain that doesn’t improve with rest, occasional fevers, or unexplained weight loss can be easy to dismiss—until they’re not. One often-overlooked culprit is spinal tuberculosis (also called tuberculous spondylitis or Pott disease). While tuberculosis is best known as a lung infection, it can affect the spine and other bones, leading to nerve compression, deformity, and disability if not treated early. In this comprehensive guide, we break down the types of spinal tuberculosis, what leads to symptoms, and how doctors diagnose and treat the condition. You’ll learn the classic patterns (paradiscal, central, anterior subligamentous, and posterior element TB), red-flag symptoms to watch for, and evidence-based treatment paths that lead most people to recovery. Along the way, we share practical tips for living well during treatment, how to protect your loved ones, and when to seek medical care. If symptoms persist beyond two weeks, consult a doctor online with Apollo24|7 for further evaluation.

Spinal Tuberculosis at a Glance

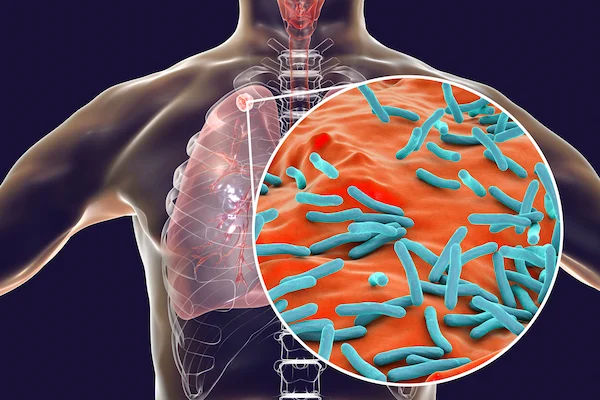

Spinal tuberculosis is an infection of the vertebrae and intervertebral discs by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It’s the most common form of skeletal TB and is often referred to as Pott disease. The thoracic and lumbar regions are most frequently affected, partly because of blood flow patterns that deliver bacteria to these parts of the spine. While tuberculosis primarily attacks the lungs, the bacteria can travel through the bloodstream, lodging in the spine and triggering a slow, destructive process in bones and discs.

How common is spinal involvement? Roughly half of all skeletal TB occurs in the spine; overall, spinal TB is a small fraction of total TB cases but carries a higher risk of disability due to spinal deformity and nerve injury if diagnosis is delayed. In countries where TB is common, spinal tuberculosis is a leading cause of chronic back pain with neurological complications.

Who is at higher risk? People with weakened immunity (HIV infection), diabetes, chronic kidney disease, malnutrition, or those on long-term steroids are more vulnerable to extrapulmonary TB, including spinal disease. Children may present earlier with deformities because their spines are still growing. A key takeaway: in regions with high TB prevalence, persistent back pain plus systemic symptoms like low-grade fever or weight loss should prompt evaluation for spinal tuberculosis. If symptoms persist beyond two weeks, consult a doctor online with Apollo 24|7 for further evaluation.

Consult Top Lung Specialists

What Leads to Spinal TB? Pathways and Risk Factors

The path to spinal tuberculosis usually begins with a lung infection (sometimes silent). From there, TB bacteria spread through the bloodstream or the valveless Batson venous plexus to the vertebral bodies, especially the thoracic and lumbar segments. Once the bacteria lodge in the bone marrow adjacent to the endplates, they cause granulomatous inflammation and caseation necrosis that weaken the bone, disc, and supporting ligaments.

Host factors amplify risk:

• Immune suppression, particularly HIV, increases the risk of extrapulmonary TB, including the spine.

• Diabetes, malnutrition, chronic kidney disease, and prolonged steroid or biologic therapy reduce the body’s ability to contain infection.

• Age: children are at risk of faster deformity due to pliable bones; older adults may present atypically with fewer fevers.

• Prior TB exposure or untreated latent TB increases the chance of reactivation.

Environmental and socioeconomic drivers matter too. Crowded living conditions, limited access to health care, and delayed diagnosis contribute to more advanced presentations. Smoking and indoor air pollution may worsen overall TB risk.

Types of Spinal Tuberculosis

Classifying the types of spinal tuberculosis helps clinicians predict complications and plan treatment. The main patterns include:

• Paradiscal type: The most common. Infection starts near the vertebral endplates adjacent to the disc. The disc space narrows gradually as the adjacent vertebral bodies are destroyed. Imaging often shows adjacent endplate erosion, wedging, and a paraspinal “cold” abscess. This type tends to cause angular kyphosis if not treated.

• Central vertebral body type: The infection begins within the center of a vertebral body, causing collapse (“vertebra plana” features) with relative preservation of the disc early on. This can mimic malignancy on imaging. MRI shows marrow oedema and central destruction.

• Anterior subligamentous spread: Infection tracks beneath the anterior longitudinal ligament, moving across multiple levels. This can produce long, thin paravertebral abscesses and multi-level involvement without severe early disc destruction, sometimes called “skip lesions” when noncontiguous levels are affected.

• Posterior element (appendiceal) TB: Atypical but important. The infection involves pedicles, laminae, spinous processes, or facets. Patients often present with posterior neck or back pain and early neurologic symptoms due to canal encroachment, while X-rays may look deceptively normal. MRI is essential to detect this pattern.

• Atypical patterns: Noncontiguous (skip) spinal tuberculosis means two or more separate areas of the spine are diseased with normal segments in between. Although less common, recognising this prevents missed lesions on imaging. Noncontiguous involvement has been reported in a minority of patients and should be suspected if symptoms don’t match a single-level finding.

Symptoms and Warning Signs You Shouldn’t Ignore

Spinal TB is a slow burner. Early symptoms are subtle:

• Persistent back pain or stiffness that worsens over weeks to months, often worse at night or with movement.

• Local tenderness over the spine and muscle spasm.

• Fatigue, reduced appetite, and low energy.

Systemic signs—especially in the context of a TB exposure or in a high-prevalence area—include:

• Low-grade fever, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss.

• A soft, painless swelling near the spine or in the groin/lower abdomen (a “cold abscess”), sometimes extending as a psoas abscess.

Neurological red flags (urgent):

• Weakness in the legs or arms, numbness, tingling, or gait imbalance.

• New bowel or bladder problems (urgency, retention, incontinence).

• Severe, unremitting pain that wakes you from sleep or a rapidly worsening curve (kyphosis).

Consult Top Lung Specialists

Children vs adults: Children are prone to quicker deformity because their vertebrae are softer. They may present with a visible spinal curve, irritability, or refusal to walk. Adults more commonly report chronic back pain and systemic symptoms.

Diagnostic delays are common because early symptoms resemble mechanical back pain. One Indian cohort review found that earlier initiation of anti-TB therapy significantly reduced the risk of severe kyphosis and neurological complications compared with delayed diagnosis [6]. If back pain persists beyond two weeks, especially with fever or weight loss, consult a doctor with Apollo 24|7. If neurological signs develop (weakness, numbness, bowel/bladder changes), seek urgent in-person care.

Why Timely Care Matters: Complications and Outcomes?

Spinal tuberculosis can be devastating without timely care:

• Kyphosis and spinal deformity: Collapse of the anterior vertebral bodies leads to a forward bend (kyphotic angulation). In children, progressive deformity can continue even after disease control due to growth imbalance, sometimes requiring corrective surgery.

• Pott’s paraplegia: Compression of the spinal cord or nerves from bone fragments, disc material, or abscess can cause weakness or paralysis. Early anti-TB therapy (ATT) and, when indicated, decompression surgery can reverse deficits in many patients if started promptly.

• Cold abscesses: Paraspinal or psoas abscesses may grow silently, presenting as a groin swelling or abdominal lump. Drainage plus ATT is often required when abscesses are large or symptomatic.

• Chronic pain and recurrence: With modern therapy, cure rates are high. However, delayed diagnosis increases the chance of residual deformity, chronic pain, and reduced quality of life.

How Doctors Diagnose Spinal Tuberculosis?

Diagnosis blends clinical suspicion, imaging, and laboratory confirmation.

• Exam and risk stratification: Doctors assess pain location, tenderness, posture, gait, and neurological function. Context matters: TB exposure, prior TB, immunosuppression, or origin from a TB-endemic region raises suspicion.

Imaging:

• X-ray: May be normal early. Later, shows vertebral endplate erosion, disc space narrowing (paradiscal TB), and angular kyphosis.

• MRI (preferred): Best for early detection. Shows bone marrow edema, endplate destruction, disc involvement, epidural extension, and paraspinal abscesses. Posterior element disease and subtle epidural collections are well seen.

• CT: Excellent for bony detail and planning biopsy/drainage. Detects sequestra (dead bone) and cortical destruction.

What MRI shows in different types:

• Paradiscal: Adjacent endplate marrow edema, disc involvement, paraspinal soft tissue.

• Central type: Predominant vertebral body edema and collapse with relatively preserved disc early on.

• Anterior subligamentous: Multi-level prevertebral soft-tissue collection tracking under the anterior ligament.

• Posterior element TB: Pedicle/lamina marrow signal change with posterior soft tissue and canal compromise.

Lab tests:

• ESR and CRP are usually elevated but not specific; they help monitor response over time.

• TB immunologic tests (IGRA/TST) support the diagnosis but cannot distinguish active from latent disease alone.

• Microbiology and histology are key: Image-guided needle biopsy or surgical samples allow acid-fast staining, Xpert MTB/RIF (rapid molecular test for TB and rifampicin resistance), culture, and histopathology. WHO recommends Xpert MTB/RIF for extrapulmonary TB specimens to improve rapid diagnosis and detect drug resistance.

Treatment That Works: Medicines, Bracing, and Surgery

Anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) is the cornerstone. A standard rifampicin-based regimen is used, typically with an intensive phase (multiple drugs) followed by a continuation phase. Many authorities support 6–12 months of therapy for spinal TB, with duration tailored to clinical, radiologic, and microbiologic response and the presence of complications. Clinical improvement (less pain, better mobility), down-trending ESR/CRP, and resolution of abscesses on imaging help guide duration. Drug susceptibility testing (via Xpert MTB/RIF and culture) is important to detect resistance.

When is surgery needed?

• Progressive or severe neurological deficit (cord compression).

• Spinal instability or significant deformity (e.g., worsening kyphosis).

• Large abscess not responding to medical therapy alone.

• Failure of medical therapy or diagnostic uncertainty requiring open biopsy.

Surgical goals include decompression of the neural elements, drainage of abscesses, debridement of infected tissue, and stabilisation with instrumentation when needed. In many cases, early ATT without surgery is sufficient if there is no neurological compromise or instability.

Bracing, pain control, nutrition, and physiotherapy:

• A thoracolumbar brace can reduce pain and support healing by limiting motion during the active phase.

• Analgesics and careful activity modification help maintain function.

• Nutrition matters: adequate protein, vitamin D, calcium, and micronutrients support bone healing and immune function. If lab tests are needed (e.g., vitamin D), Apollo 24|7 offers home collection services.

• Physiotherapy restores mobility and strength as pain improves. Avoid heavy lifting until your doctor clears you.

Monitoring and safety:

• Side effects of ATT (e.g., liver inflammation) need monitoring. Report jaundice, severe nausea, or dark urine promptly.

• Regular follow-up every 4–8 weeks early on helps track recovery.

Living Well During Recovery and Preventing Spread

Daily life during treatment:

• Activity: Gentle mobility is better than prolonged bed rest. Short walks, posture awareness, and core-strengthening (as advised) support recovery.

• Work and school: Many people resume light work within weeks once pain is controlled; heavy manual labour may need to wait until the spine stabilises. Talk to your doctor about a phased return.

Nutrition for bone healing and immunity:

• Prioritise protein (dals, eggs, dairy, lean meats), fruits/vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats.

• Vitamin D and calcium are essential for bone health. If unsure about your levels, discuss testing.

Preventing transmission:

• Spinal TB itself is not contagious unless there is concurrent pulmonary TB. If you have cough or respiratory symptoms, your clinician may test your sputum.

• Good cough etiquette, ventilation, and masks reduce risk if pulmonary TB is present. Household contacts might need screening per local guidelines [4][5].

Preventing relapse:

• Complete your full course of ATT, even when you feel better.

• Keep all follow-up appointments and imaging checks.

• Red flags after recovery: return of night pain, fever, or new neurological symptoms.

If your condition does not improve after trying these methods, book a physical visit to a doctor with Apollo 24|7 for further evaluation.

Spinal TB vs Other Causes of Back Pain

Mechanical back pain (muscle strain, degenerative discs) often improves within days to weeks with rest, gentle movement, and pain relief. In contrast, tuberculous spondylitis tends to persist and gradually worsen, often with night pain and weight loss. Pyogenic (bacterial) spondylodiscitis typically has a more acute onset with higher fevers and elevated white blood cell counts; MRI tends to show more aggressive disc space destruction earlier, while TB often shows larger paraspinal collections and slower disc involvement.

Red flags for urgent imaging and referral:

• Back pain with fever, night sweats, or unintended weight loss.

• Neurological symptoms: weakness, numbness, or bowel/bladder changes.

• History of TB exposure, HIV, diabetes, or immunosuppression.

• Pain lasting more than two weeks without improvement.

A practical rule: If pain persists beyond two weeks or is accompanied by red flags, ask your clinician about MRI and TB testing. Apollo 24|7 can help coordinate an online consult and appropriate referrals.

Consult Top Lung Specialists

Conclusion

Spinal tuberculosis is both a medical and a time challenge: the earlier it’s identified, the better the outcomes. Understanding what leads to spinal TB—the routes bacteria take, the types of disease patterns, and the symptoms to watch for—helps you seek care promptly. MRI and targeted tests such as Xpert MTB/RIF are critical to confirming the diagnosis and tailoring treatment. The good news is that most people do well on modern anti-tubercular regimens, and many never need surgery if treatment starts early. Bracing, nutrition, and physiotherapy support healing, while regular follow-ups ensure the infection is clearing and the spine stays stable. If you’ve had back pain for more than two weeks, especially with fever, night sweats, or weight loss, consult a doctor online with Apollo 24|7 for further evaluation. And if your condition isn’t improving as expected, book a physical visit to a doctor with Apollo 24|7 to reassess your plan. With timely care and support, spinal TB is treatable—and a full, active life is achievable.

Consult Top Lung Specialists

Dr. Ravi Charan Avala

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

3 Years • DNB, DTCD

Chinagadila

Apollo Hospitals Health City Unit, Chinagadila

(25+ Patients)

Dr. Sumara Maqbool

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

12 Years • MBBS, DNB Respiratory, critical care and sleep medicine, DrNB superspeciality Critical care, IDCCM, IFCCM, EDIC

Delhi

Apollo Hospitals Indraprastha, Delhi

(25+ Patients)

Dr. R. Nithiyanandan

Pulmonology/critical Care Specialist

6 Years • MBBS, MD Internal Medicine , DM Pulmonary and critical care medicine

Chennai

Apollo Hospitals Greams Road, Chennai

(50+ Patients)

Dr. Dawar Masud Rizavi

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

26 Years • MBBS, MD (Respiratory Diseases & TB) MRCP (London, UK)

Lucknow

Apollomedics Super Speciality Hospital, Lucknow

Dr. Tamal Bhattacharyya

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

8 Years • MBBS, MD (Respiratory Medicine)

Kolkata

MCR SUPER SPECIALITY POLY CLINIC & PATHOLOGY, Kolkata

Consult Top Lung Specialists

Dr. Ravi Charan Avala

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

3 Years • DNB, DTCD

Chinagadila

Apollo Hospitals Health City Unit, Chinagadila

(25+ Patients)

Dr. Sumara Maqbool

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

12 Years • MBBS, DNB Respiratory, critical care and sleep medicine, DrNB superspeciality Critical care, IDCCM, IFCCM, EDIC

Delhi

Apollo Hospitals Indraprastha, Delhi

(25+ Patients)

Dr. R. Nithiyanandan

Pulmonology/critical Care Specialist

6 Years • MBBS, MD Internal Medicine , DM Pulmonary and critical care medicine

Chennai

Apollo Hospitals Greams Road, Chennai

(50+ Patients)

Dr. Dawar Masud Rizavi

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

26 Years • MBBS, MD (Respiratory Diseases & TB) MRCP (London, UK)

Lucknow

Apollomedics Super Speciality Hospital, Lucknow

Dr. Tamal Bhattacharyya

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

8 Years • MBBS, MD (Respiratory Medicine)

Kolkata

MCR SUPER SPECIALITY POLY CLINIC & PATHOLOGY, Kolkata

Consult Top Lung Specialists

Dr. Ravi Charan Avala

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

3 Years • DNB, DTCD

Chinagadila

Apollo Hospitals Health City Unit, Chinagadila

(25+ Patients)

Dr. Sumara Maqbool

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

12 Years • MBBS, DNB Respiratory, critical care and sleep medicine, DrNB superspeciality Critical care, IDCCM, IFCCM, EDIC

Delhi

Apollo Hospitals Indraprastha, Delhi

(25+ Patients)

Dr. R. Nithiyanandan

Pulmonology/critical Care Specialist

6 Years • MBBS, MD Internal Medicine , DM Pulmonary and critical care medicine

Chennai

Apollo Hospitals Greams Road, Chennai

(50+ Patients)

Dr. Dawar Masud Rizavi

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

26 Years • MBBS, MD (Respiratory Diseases & TB) MRCP (London, UK)

Lucknow

Apollomedics Super Speciality Hospital, Lucknow

Dr. Tamal Bhattacharyya

Pulmonology Respiratory Medicine Specialist

8 Years • MBBS, MD (Respiratory Medicine)

Kolkata

MCR SUPER SPECIALITY POLY CLINIC & PATHOLOGY, Kolkata

More articles from Tuberclosis

Frequently Asked Questions

1) What are the most common types of spinal tuberculosis?

The main types are paradiscal (adjacent to the disc), central vertebral body, anterior subligamentous spread, and posterior element TB. Recognising these types helps guide diagnosis and treatment planning.

2) How is spinal TB diagnosed?

Doctors use MRI for early detection and image-guided biopsy for Xpert MTB/RIF and culture to confirm TB and check drug resistance. ESR/CRP help monitor recovery. If you have persistent back pain with systemic symptoms, ask about MRI and biopsy-based diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis.

3) How long is treatment for spinal TB?

Most patients receive 6–12 months of rifampicin-based anti-TB therapy, adjusted to response and any complications. Your clinician will tailor duration using clinical progress, labs, and follow-up imaging.

4) When is surgery needed for tuberculous spondylitis?

Surgery is considered for neurological deficits (e.g., weakness from cord compression), spinal instability, significant deformity, large abscesses, or when medical therapy fails. Otherwise, many cases respond to medicines and bracing.

5) Is spinal TB contagious?

Spinal TB itself isn’t typically contagious. However, if you also have pulmonary TB, you can transmit TB through coughing. Your clinician may screen for lung involvement and advise on protecting household contacts.