Guide to Tace Transarterial Chemoembolization

Discover everything you need to know about Holter monitoring in this complete guide. Learn how it differs from a standard ECG and when doctors recommend it. Understand the symptoms that prompt testing and how the device records heart activity. Find out what your results mean and how they help diagnose heart rhythm issues.

Written by Dr. Dhankecha Mayank Dineshbhai

Reviewed by Dr. Rohinipriyanka Pondugula MBBS

Last updated on 13th Jan, 2026

Introduction

If you or a loved one has liver cancer, you may hear your doctor recommend TACE—short for transarterial chemoembolization. This minimally invasive procedure delivers chemotherapy directly into the artery feeding a tumor and then blocks that artery, starving the tumor of blood. Because TACE is delivered inside the liver rather than throughout the body, it can focus therapy where it’s needed most while limiting overall side effects. In this guide, we explain how TACE works, who it helps most, what to expect before and after the procedure, common side effects, and how TACE fits with other treatments such as immunotherapy, surgery, ablation, or Y‑90 radioembolization. Whether you’re exploring TACE for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), using it as a bridge to transplant, or considering it for other liver-dominant tumors, this guide equips you to have informed conversations and make confident decisions.

Consult Top Oncologists

What is TACE (Transarterial Chemoembolization)?

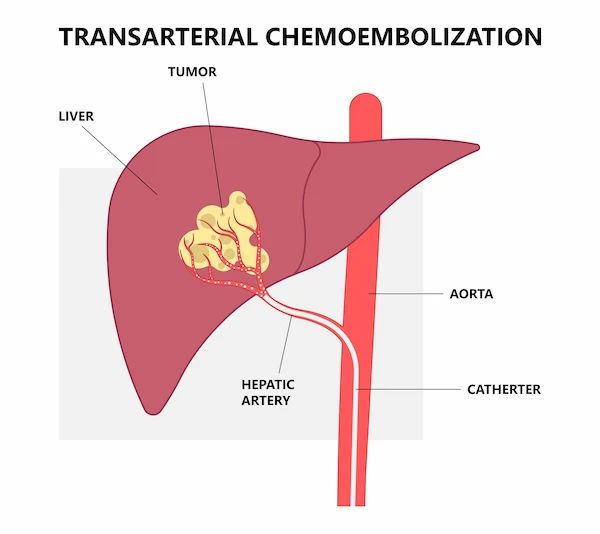

TACE is a targeted liver cancer treatment performed by an interventional radiologist. In simple terms, it’s a “dual-hit” therapy: a high dose of chemotherapy is infused directly into the artery feeding the tumor, and then tiny particles are injected to plug that artery (embolization). The result is that tumor cells get a concentrated dose of chemo and simultaneously lose their blood supply. Because normal liver tissue can also receive blood from the portal vein, healthy areas are relatively spared, while tumors which rely heavily on arterial blood are more vulnerable.

Two main types are used:

- Conventional TACE (cTACE): A chemotherapy drug (often doxorubicin or cisplatin) is mixed with an oily contrast agent (lipiodol) that helps carry the drug into the tumor. This is followed by embolic particles to block the artery.

- Drug-eluting bead TACE (DEB-TACE): Tiny beads loaded with chemotherapy slowly release the drug inside the tumor while also blocking blood flow. DEB-TACE may lower systemic exposure and can reduce certain side effects in some patients, though outcomes vary by study.

TACE is most commonly used for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most frequent primary liver cancer. It can also be considered for some liver-dominant metastases (e.g., neuroendocrine tumors, colorectal cancer) or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in select cases. As a locoregional therapy, TACE is delivered via a small catheter inserted through an artery in the wrist or groin and navigated into the liver under X-ray guidance. The procedure is usually done under conscious sedation or light anesthesia, and many patients go home the next day.

Unique insight: Think of TACE like turning off the “tap” that feeds the tumor while pouring in a targeted “cleaning agent.” It’s the combination that makes TACE different from simple chemo or simple embolization alone.

How TACE works: the dual-hit approach

- Direct intra-arterial chemotherapy gives higher local concentration than IV chemo.

- Embolization cuts off oxygen and nutrients (ischemia), increasing tumor kill.

- Normal liver has dual blood supply; tumors depend more on the hepatic artery, which TACE targets.

Conventional vs DEB-TACE

- cTACE uses lipiodol plus embolic particles; DEB-TACE uses drug-loaded beads.

- Some centers favor DEB-TACE for more standardized dosing; others prefer cTACE for flexibility and radiographic

lipiodol mapping. - Your team chooses based on tumor features, liver function, and center experience [3][4][7].

Who is TACE for? Indications, staging, and candidacy

Most guidelines recommend TACE for patients with intermediate-stage HCC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, BCLC

stage B): multifocal tumors without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread, and with preserved liver function

(typically Child-Pugh A or early B). TACE may also be used as:

- Bridging therapy: To keep a tumor controlled while waiting for a liver transplant.

- Downstaging therapy: To shrink tumors so a patient becomes eligible for transplant.

- Part of combination therapy: With ablation, surgery, or systemic drugs depending on disease course.

Assessing candidacy involves:

- Liver function: Child-Pugh score, MELD score, bilirubin, albumin.

- Tumor factors: Size, number, location, vascular invasion (portal vein thrombosis), and whether disease has spread

outside the liver. - Performance status (how well you’re functioning day-to-day).

Vascular anatomy: Can the interventional radiologist safely reach and selectively treat the tumor-feeding arteries?

When is TACE not recommended?

Absolute contraindications include decompensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh C), severe liver failure, uncontrolled infection,

or lack of arterial access. Relative contraindications include significant portal vein thrombosis, poor kidney function,

severe coagulopathy, or bile duct obstruction though in experienced hands, carefully selected patients can sometimes

still be treated or offered alternatives like Y‑90 radioembolization.

BCLC staging overview

- BCLC A (early): Curative options (surgery, ablation, transplant).

- BCLC B (intermediate): TACE is standard of care in many cases [3][4].

- BCLC C (advanced): Systemic therapies; TACE may be considered selectively.

- BCLC D (terminal): Best supportive care.

Bridging and downstaging to transplant

TACE can reduce dropout from waiting lists by controlling tumor growth.

Downstaging protocols use TACE to bring tumor burden within transplant criteria; success depends on initial tumor

load and liver reserve.

Who is not a candidate

- Advanced decompensated cirrhosis, severe jaundice, refractory ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy.

- Extensive tumor burden replacing most of the liver, or poor arterial access.

- Uncontrolled systemic illness or pregnancy (individualized assessment needed) [3][4].

Preparing for the procedure

Preparation ensures safety and maximizes effectiveness. You’ll typically undergo:

- Imaging: Contrast-enhanced MRI or CT to map tumor size, number, and arterial supply.

- Labs: Liver function tests (AST/ALT, bilirubin, albumin), kidney function (creatinine), clotting (INR, platelets), and

tumor markers like AFP. If you need convenient testing, Apollo24|7 offers home collection for common labs, which

can help speed pre-procedure evaluation. - Medical review: Current medications, allergies (especially to contrast dye), and prior liver treatments are reviewed by

the interventional radiologist and the multidisciplinary team.

Medications to discuss:

- Blood thinners (warfarin, DOACs): Often paused or bridged to lower bleeding risk.

- Metformin: May be held around the time of contrast use in some patients with kidney risk.

- Immunotherapy/targeted therapy: Your oncology team may coordinate timing to reduce overlapping toxicities.

- Herbal supplements: Some affect bleeding or liver function; disclose all usage.

Diet and hydration:

- You may be asked to fast for several hours before TACE.

- Adequate hydration reduces kidney stress from contrast dye.

Medications to stop or adjust

- Anticoagulants/antiplatelets as guided by your team.

- Review diabetic meds and nephrotoxic agents.

- Avoid NSAIDs if possible around the procedure to protect kidneys unless advised.

Step-by-step: What happens on the day

- Admission and consent: You’ll review risks, benefits, and alternatives and sign consent forms.

- Sedation and access: Depending on center practice, you’ll receive local anesthesia plus light sedation. The

interventional radiologist accesses an artery—commonly the femoral artery in the groin or the radial artery in the

wrist—to insert a slender catheter. - Mapping and delivery: Using live X-ray (fluoroscopy) and contrast dye, the radiologist steers microcatheters into the

branches feeding the tumor. The chemotherapy agent is infused, followed by embolic materials (lipiodol plus particles

for cTACE, or drug-eluting beads for DEB-TACE). - Duration: Most procedures take 60–120 minutes, depending on anatomy and the number of tumors.

- Recovery: After catheter removal, pressure is applied to prevent bleeding. Expect a few hours of monitoring. Many

patients stay overnight for observation and symptom control (nausea, pain), then go home the next day with

medications and instructions.

Anesthesia and catheter access

- Conscious sedation vs. general anesthesia depends on patient factors and center protocols.

- Femoral vs. radial access may influence post-procedure mobility.

Chemo agents and embolic materials

- Doxorubicin, cisplatin, or irinotecan (particularly in metastatic colorectal cancer) are commonly used in TACE

regimens; drug choice varies by tumor type and center [3][6]. - Embolics range from calibrated microspheres to lipiodol emulsions.

Quality of life:

- Many patients return to regular activities within a week or two.

- Post-embolization syndrome is common but usually manageable with medications and rest.

Combining therapies:

- TACE with ablation (e.g., radiofrequency or microwave) can improve local control for certain tumors, especially when

used synergistically for medium-sized lesions. - Integration with systemic therapies (e.g., immunotherapy such as atezolizumab-bevacizumab, or TKIs like

sorafenib/lenvatinib) is evolving; some centers alternate or sequence treatments based on response and tolerance.

Response rates, survival, and quality of life

- Randomized data and meta-analyses have shown survival benefits in selected patients; best outcomes occur in those

with preserved liver function and limited tumor burden. - Symptom control and delay of progression are common clinical goals.

TACE as part of combined therapy

Consider a combined or staged approach for borderline candidates, integrating ablation or systemic therapy when

appropriate.

Risks, side effects, and recovery

- Common side effects (post-embolization syndrome):

- Fatigue, low-grade fever, abdominal pain or cramping, nausea/vomiting, reduced appetite typically peaking in the first

48–72 hours and improving within a week.

Less common but important risks:

- Liver injury or failure, especially in patients with advanced cirrhosis.

- Infection/abscess (higher risk with bile duct abnormalities).

- Ulcers in the stomach/duodenum or gallbladder inflammation if non-target vessels are affected.

- Contrast-related kidney stress or allergic reactions.

- Vascular complications at the access site (bleeding, pseudoaneurysm) [1][5].

Post-embolization syndrome and management

- Medications: antiemetics, antipyretics, and pain control.

- Diet: bland, low-fat meals; hydrate well.

- Expect fatigue—rest and light movement balance is key.

Serious but less common risks

- Your team works to prevent non-target embolization with careful catheter placement and imaging.

- Report new, focal abdominal pain immediately—it could signal gallbladder or GI irritation.

H3: At-home recovery timeline and diet

- Day 1–3: strongest symptoms; prioritize rest and hydration.

- Day 4–7: gradual improvement; resume light duties as tolerated.

- Week 2+: most return to baseline, but individual recovery varies.

H2: Aftercare: Follow-up, scans, and repeat TACE

Follow-up is essential to assess response and guide next steps:

- Imaging: Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI is commonly done 4–8 weeks after TACE to check for residual tumor

enhancement (a sign of active tumor). Subsequent scans may be spaced every 2–3 months initially [3][4][6].

- Labs: Liver function and AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) are tracked to monitor liver health and tumor activity. Apollo24|7

offers home collection for AFP and LFTs, which can be convenient between clinic visits.

- Decision points: If imaging shows residual viable tumor and your liver function is preserved, your team may

recommend repeat TACE (often termed “on-demand” TACE). Alternatively, if the tumor does not respond or liver

function declines, it may be time to switch to systemic therapy or consider other locoregional options [3][4][6].

How many TACEs are typical?

There’s no fixed number. Many centers individualize therapy, repeating TACE until there’s no more targetable disease

or until risks outweigh benefits. Some adopt “TACE refractoriness” criteria to decide when to stop and transition to

other treatments.

Imaging schedule (CT/MRI) and lab markers (AFP)

- First scan at ~4–8 weeks; subsequent scans every 2–3 months early on.

- AFP trends can support imaging findings but are not a substitute.

When to repeat or switch therapy

- Repeat if viable tumor persists and liver function is adequate.

- Switch to systemic therapy or alternative locoregional options if progression occurs or if TACE becomes intolerable.

Alternatives and comparisons (brief overview)

- Y‑90 radioembolization (TARE) can be preferable in some cases (e.g., portal vein thrombosis), with different side-effect

profiles [2][6][8]. - Ablation is often curative for small lesions; surgery or transplant when feasible remains the gold standard.

Alternatives to TACE and how they compare

While TACE is a cornerstone for intermediate-stage HCC, alternatives may be better for specific patients:

- Y‑90 radioembolization (TARE): Delivers radiation microspheres via the hepatic artery. Often considered when portal

vein thrombosis is present, as it tends to spare more normal liver function. Side effects can be milder than TACE in

some patients, though outcomes are influenced by tumor and liver factors [2][6][8]. - Ablation (RFA/MWA): Best for small tumors (often ≤3 cm), potentially curative. Sometimes combined with TACE for

intermediate-sized lesions to enhance local control. - Surgery (resection): Curative in selected patients with good liver function and localized disease.

- Liver transplant: Curative for eligible patients with early-stage disease meeting criteria; TACE often serves as bridging

or downstaging therapy. - Systemic therapy: Targeted drugs (e.g., sorafenib, lenvatinib) and immunotherapy combinations (e.g., atezolizumab-

bevacizumab) are standard for advanced disease or after locoregional treatments no longer control tumor growth [2][6].

Conclusion

TACE, or transarterial chemoembolization, offers a focused way to treat liver tumors by delivering chemotherapy right

where it’s needed and cutting off the tumor’s blood supply. For many people with intermediate-stage HCC and stable liver function, it improves tumor control and can extend survival. It’s also a valuable bridge or downstaging tool for those awaiting transplant. Like any procedure, TACE has risks most commonly short-term fatigue, fever, nausea, and pain but serious complications are uncommon in experienced centers, and most patients resume daily routines within a week or two.

The key to success is individualized care: matching the right treatment to your stage, liver health, and goals, then reassessing after follow-up imaging. If TACE isn’t the best fit, alternatives such as Y‑90 radioembolization, ablation, surgery, transplantation, or systemic therapy can play central roles. Keep communication open with your team, plan your recovery at home, and don’t hesitate to ask questions.

Consult Top Oncologists

Consult Top Oncologists

Dr Gowshikk Rajkumar

Oncologist

10 Years • MBBS, DMRT, DNB in Radiation oncology

Bengaluru

Apollo Clinic, JP nagar, Bengaluru

Dr.sanchayan Mandal

Medical Oncologist

17 Years • MBBS, DrNB( MEDICAL ONCOLOGY), DNB (RADIOTHERAPY),ECMO. PDCR. ASCO

Kolkata

Dr. Sanchayan Mandal Oncology Clinic, Kolkata

Dr. Sanchayan Mandal

Medical Oncologist

17 Years • MBBS, DNB Raditherapy, DrNB Medical Oncology

East Midnapore

VIVEKANANDA SEBA SADAN, East Midnapore

Dr. Gopal Kumar

Head, Neck and Thyroid Cancer Surgeon

15 Years • MBBS, MS , FARHNS ( Seoul, South Korea ), FGOLF ( MSKCC, New York )

Delhi

Apollo Hospitals Indraprastha, Delhi

(25+ Patients)

Dr. Raja T

Oncologist

20 Years • MBBS; MD; DM

Chennai

Apollo Hospitals Greams Road, Chennai

(200+ Patients)

Consult Top Oncologists

Dr Gowshikk Rajkumar

Oncologist

10 Years • MBBS, DMRT, DNB in Radiation oncology

Bengaluru

Apollo Clinic, JP nagar, Bengaluru

Dr.sanchayan Mandal

Medical Oncologist

17 Years • MBBS, DrNB( MEDICAL ONCOLOGY), DNB (RADIOTHERAPY),ECMO. PDCR. ASCO

Kolkata

Dr. Sanchayan Mandal Oncology Clinic, Kolkata

Dr. Sanchayan Mandal

Medical Oncologist

17 Years • MBBS, DNB Raditherapy, DrNB Medical Oncology

East Midnapore

VIVEKANANDA SEBA SADAN, East Midnapore

Dr. Gopal Kumar

Head, Neck and Thyroid Cancer Surgeon

15 Years • MBBS, MS , FARHNS ( Seoul, South Korea ), FGOLF ( MSKCC, New York )

Delhi

Apollo Hospitals Indraprastha, Delhi

(25+ Patients)

Dr. Raja T

Oncologist

20 Years • MBBS; MD; DM

Chennai

Apollo Hospitals Greams Road, Chennai

(200+ Patients)

More articles from Liver Cancer

Frequently Asked Questions

1) Is TACE a cure for liver cancer?

Not usually. TACE controls tumor growth and can extend survival, especially in intermediate-stage HCC, but it’s typically not curative. It can bridge to curative options like transplant or combine with ablation for small tumors.

2) How long is recovery after TACE?

Many people feel better within 5–7 days, with fatigue and mild pain gradually improving. Plan a lighter schedule for the first week and follow your team’s guidance on activity.

3) What is the difference between DEB‑TACE and conventional TACE?

Conventional TACE uses a chemo–lipiodol mixture followed by particles; DEB‑TACE uses drug-eluting beads that release chemotherapy slowly. Choice depends on patient factors and center experience.

4) How do doctors know if TACE worked?

A contrast-enhanced CT or MRI 4–8 weeks after TACE checks for “enhancing” (active) tumor. Labs like AFP support imaging. Depending on results, you may repeat TACE or switch therapies.

5) Can TACE be used if I have portal vein thrombosis?

It depends on the extent. Main PVT can increase risk with TACE; some patients may be better candidates for Y‑90 radioembolization. Your team will assess imaging and liver function to guide you.